Escaping the Trauma of the Hero’s Journey

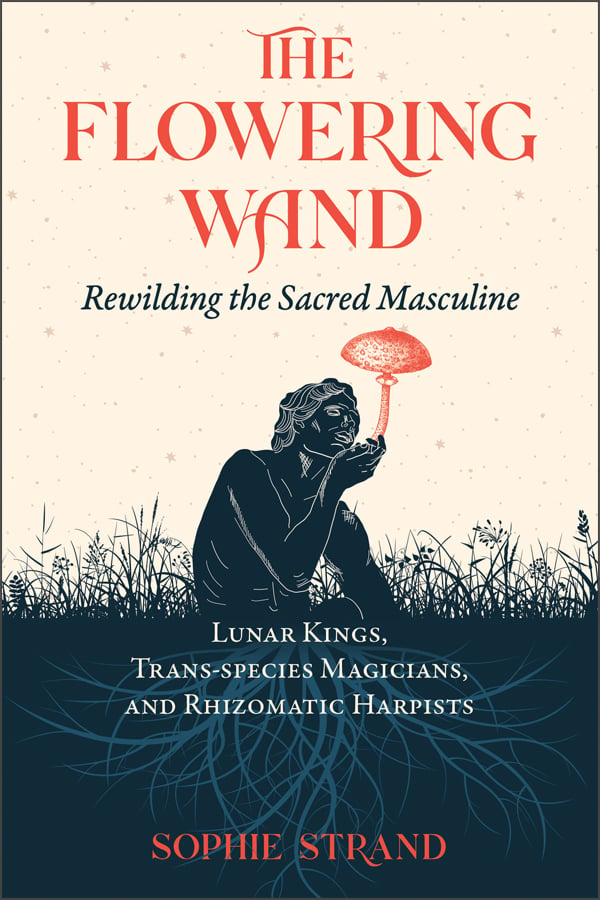

From The Flowering Wand: Rewilding the Sacred Masculine by Sophie Strand

Tristan is dying to escape. Literally dying or trying to. He throws himself off cliffs, out of church windows, off boats, into impossible battles, and, most often, out into the dark night of a stormy ocean.

Tristan, a Dark Age romantic hero, is known for his doomed love for the Irish princess Isolde, who is married to his friend King Mark. The story plays on themes of duty and love, and the central love triangle may have formed the basis of the later Arthurian myths.

From his birth onward, Tristan is constantly running away from typical manhood. When his parents King Rivalin and Queen Blancheflor die, Tristan is adopted by a lower-rank friend of his father who hides Tristan’s real identity. As a boy he runs off (or is kidnapped by pirates after a betrayal by his stepbrothers) and washes up on the shores of Cornwall, escaping his adoptive father’s stultifying belief that Tristan must be educated and made into a “noble” knight. Tristan rises to fame in the court of King Mark (the sixth-century king of Cornwall) through a distinctly paleolithic power: his knowledge of the hunt and the ways of the deer. But the minute his royal ancestry is acknowledged and it seems he might have to become the king of Lyonesse, or worse, Mark’s heir, Tristan knows he must escape.

A musician and a trickster, Tristan does not want to ascend to patriarchal power. Instead, he gives his father’s kingdom to his adoptive father and escapes Mark’s attempt to make him an heir by throwing himself into a suicidal battle with the Irish warrior Morholt. Victorious, but fatally wounded by a poisoned sword wound in the groin, Tristan is faced with two fates: to die inside the sterile masculine archetype or to surrender to the ocean of something older and wilder. Tristan, ever the anti-hero, asks his friends to secretly send him out to sea in the middle of the night with no oars and only his harp. He leaves behind the phallic sword and puts his trust in melody, in rhythm rather than rigidity. He trusts the ocean. Most of all, he trusts his own poisoned wound. And like the Greek word pharmakon, which indicated a substance both poison and medicine, Tristan’s poison is also the medicine that will cure the traumatic wounding of a hero’s solitary journey toward domination and death.

Morholt’s sword carried a poison that leads Tristan back to the land of his original legend: Ireland. Ireland, where paganism had been semiprotected from the Romans and Christianity. Where the Goddess still knew how to transform narcissistic heroes into fertile magicians. Waiting for Tristan on the Irish shore are two women. One older, one younger, mother and daughter, they echo the older Bronze Age double goddess: Demeter and Persephone, who manifest now as Queen Isolde and her daughter Princess Isolde. The women pull him out of the ocean and wash him free of his name. When he recovers, Tristan calls himself by a new name, Tantris, and offers his service as a music teacher to the lovely princess.

So begins Tristan’s healing. He will no longer be shackled to violence and domination. By leaving behind his sword, he is transformed into an older kind of masculine archetype, one that tells a story with cunning and magic and music. What seems deeply important is that, in most of the textual versions of the legend, after this wounding and night sea journey, Tristan is no longer primarily referred to as a knight or associated with battle. No. He is most often referred to as a sorcerer, magician, or harpist. An Orpheus. A lover.

Yet sorrow is Tristan’s burden and birthright. He not only lives in sorrow, he is called it, since his name derives from the French word triste, “sorrow.” He was given his name after his mother, Blancheflor, died in childbirth following the news that her beloved husband, Rivalin, had died in battle.

How long does it take someone to outrun their name? The answer to this question, for Tristan, is famously tragic. While he evades death multiple times—poisoned by Morholt’s spear, jumping from clifftops, and escaping King Mark’s wrath when he learns his wife Isolde has betrayed him with Tristan—he cannot escape forever. Finally, wounded in a petty skirmish with neighboring tribes, Tristan dies heartbroken, fevered, and disgraced, with his beloved only miles away.

Isolde, his great love, is still married to King Mark, but hearing that Tristan is near death, she quickly hops on a boat. She is a great healer and knows she may be able to save her lover. But she is too late. Many suppose that if Isolde had made it to Tristan’s bedside in time, the talented Irish herbalist would have been able to save her beloved. But perhaps we should admit that Tristan was already doomed. There are only so many wounds—psychic and physical—someone can hold before deciding that they can’t keep walking, that they can’t keep letting the narrative roll them onward.

Mythically, we think of Tristan as a handsome knight of love, a proto-troubadour with shiny armor and luscious locks. Gottfried von Strassburg describes him as “smooth and soft,” with hands as “white as ermine.” King Mark’s fascination with Tristan’s wit and beauty always borders on erotic, as does the enchantment of Tristan’s tutor, Governal, and his friend Caerdin. His allure is playful androgyny. He is both pretty and quick. Boyish, but mature in battle and bed. He plays the harp and often disguises himself as a fool. He invites role reversals from his lovers, the most memorable episode being when Isolde surprises Tristan taking a bath and threatens him with a knife to his throat.

But let us halt the story, because stories are often defense mechanisms used to distract from pain. Trauma can look like heroism. It can look like strength. Sound like beautiful music. It can be handsome and well behaved. What beautiful Tristan really represents is pain.

Tristan, born of heartbreak, dives immediately into a series of traumatic events. He is betrayed by his stepbrothers, kidnapped by pirates, and then seriously wounded by Morholt. Interestingly, Tristan seems almost relieved when he receives the “stinking” wound. His trauma, so long invisible, is finally clear to all. Everyone can see it. In fact, everyone can smell it. The wound literally emits a foul scent. He can finally rest, surrender, and put himself out to sea.

So often our wounding goes unseen and unacknowledged to the point that it becomes somatized—that is, expressed through somatic symptoms. As research into post-traumatic stress disorder has shown, a dysregulated nervous and immune system can begin to manifest real wounds to match emotional pain. Survivors of trauma and abuse are much more likely to develop terminal autoimmune and neurological disorders. It is telling that as Tristan’s psychic wounds accumulate, so do his physical wounds. Somatic experts Bessel van der Kolk and Peter Levine warn against the “desperate compulsion for reenactment.” Tristan recreates wounds to signal that he cannot continue at breakneck speed through narrative episode after episode.

Tristan’s wound is personal as well as mythic. Wounded in the groin, he calls to mind Attis and Adonis, killed by boars during the hunt. He prefigures the Fisher King and Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Amfortas, languishing in the Grail castle. But perhaps most fittingly, he reminds us of the wounded Chiron, half man and half horse. Throughout the story, Tristan tries to return to his “wilder” half by seeking out the forest or the sea. Just as Tristan’s body is wounded, so is his narrative He is a Celtic pagan hero, deeply tied to the environment, wrenched from his homeland and reinserted into a civilized Christian romance more interested in “duty” than in sacred ecology. Little surprise, then, that our hero is hobbled. His wounds are stratigraphic. Layer upon layer.

As he is thrown into one event after the other, Tristan is never allowed the slow, nonlinear, nonnarrative time it takes to heal. Words aren’t always the best way to access pain. Sometimes the story doesn’t staunch the bleeding heart. In his seminal work on somatics, Waking the Tiger, Peter Levine writes, “I learned that it was unnecessary to dredge up old memories and relive their emotional pain to heal trauma. In fact, severe emotional pain can be re-traumatizing. What we need to do to be freed from our symptoms is . . . to arouse our deep physiological resources and consciously utilize them.”

So much of the current rhetoric about healing is wedded to progress and to narrative. But the body is not a story. It is porous and complicated and changeable. It needs to dance and swim. It needs to lie on the ground for days, re-regulating its nervous system to the seasonal heartbeat of the soil. The concept of “healing” has become the time-sensitive demand of a culture bent on progressing, and unwittingly taken up by wellness and new age spiritual communities. They say we must be “integrated” and whole again; we must achieve functionality so that we can keep the narrative moving. But a body doesn’t need to move through healing. It just needs to move. And then it needs to be still. It needs to feel safe.

As we look back on centuries of violence and oppression and begin to confront the very real wounds we have inflicted on the land and on each other, it is important that we don’t try to accelerate through the difficulty. We must, as Donna Haraway so elegantly puts it, “stay with the trouble.” Ultimately, sorrow is not healed. It is held. It is honored. It is melted and blended. It moves with the body, not through linear episodes, but through slow, conscious, spiraled dance. As men acknowledge the harm they have done to others and to each other, it is important that they check in with their bodies and the greater body of the earth. Let us take Tristan and put him on a hill with a cup of tea. Let us tell him he can be still for as long as he likes. For right now, he doesn’t need to save anybody. He doesn’t even need to save himself.

|

|

|

|

|