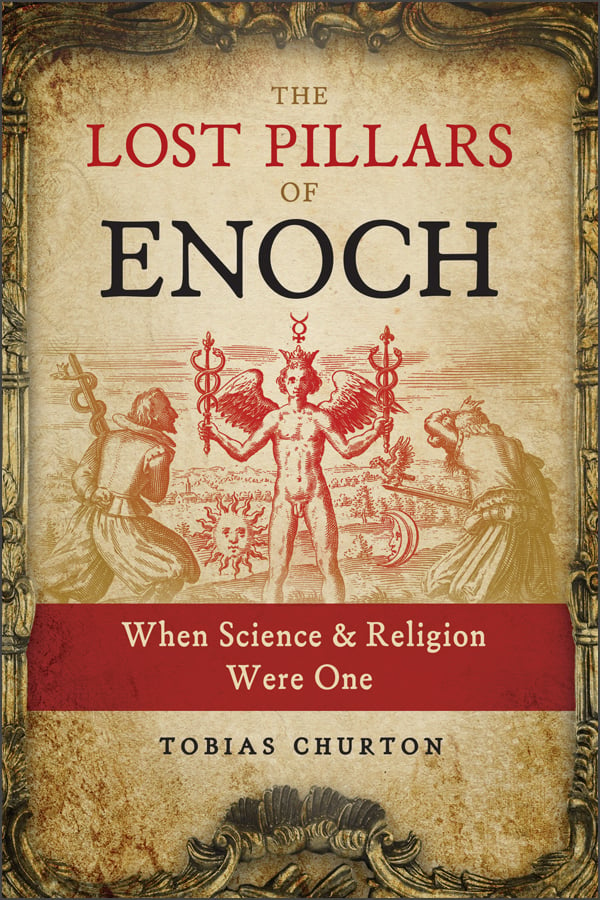

by Tobias Churton, author of The Lost Pillars of Enoch: When Science and Religion Were One and many other books

First published in 1737, William Whiston’s The Genuine Works of Flavius Josephus has long helped people fill out the accounts of Jewish history found in the Bible with Josephus’s sometimes complementary records set down during the “eighties” of the first century CE.

One striking story to appear in Josephus’s Antiquities of the Jews was unknown to the Bible. Josephus tells us of two pillars: one brick, one stone, on which the descendants of Seth (Adam’s third son) inscribe all they’ve learned of astronomy, to save the knowledge from a coming destruction of the earth by either fire or water, prophesied by God to Adam and passed on to his descendants. If it was flood, a stone pillar would still stand to testify to what others had achieved.

Josephus places the story as part of his Noah’s Flood account. Noah shows a similar respect for God to that displayed by his great grandfather Enoch, who, Genesis tells us, “walked with God”. In fact, Enoch was so close to God that he did not die on earth, or indeed, we may surmise, ever. “God took him,” we are informed bluntly, presumably to heaven.

Accompanying Genesis’s account of the lead-up to the Flood (Genesis 6:1-8) is a complex of roughly juxtaposed narrative elements, assembled and/or edited apparently to account for the corruption and ensuing punishment. Not surprisingly, the ambiguity of these elements has stimulated speculation, much of it extravagant, about giants (the “nephilim”), “sons of God,” and fallen angels on earth.

It will be noted that Josephus—a for-his-time quite rational assessor of Jewish history—holds no place in his narrative for apocalyptic implications of the type central to the apocryphal First Book of Enoch’s “Book of the Watchers.” This may well be because for Josephus, hot-headed apocalyptic hopes had, in his experience, led to what he came to consider the “banditry” of the Jewish Revolt of 66-73 CE, a hopeless insurrection crushed by Roman forces.

In Josephus’s rational hands, the pillars of Sethite knowledge receive an almost universalist colouring, the story presented for its educative value as, arguably, the world’s first story of archaeology. Indeed, by placing his story within a timespan of observable history, Josephus demonstrates a desire to root it in reality. He does this by highlighting a still observable historic artefact.

This artefact provides the true start of my narrative in The Lost Pillars of Enoch.

Josephus informs his readers that a surviving pillar could still be seen in the land of what his translator calls “Siriad”. The original Greek text, however, has “Seirida.” Apparently attempting to conflate later Latin with an earlier Greek version of Josephus’s text, translator Whiston appears to have taken the word to mean “Syria.” Whiston was aware that Greek historian Herodotus had also written about ancient stelae still visible. This leads Whiston to compound his error. Herodotus referred to stelae erected in Syria by, as he supposed, Egyptian king Sesostris (possibly Senusret III, ca. 1862-1844 BCE). Whiston felt sure Josephus had confused this reference to “Sesostris” with the biblical “Seth,” highlighting his “discovery” in a footnote.

In fact, Herodotus had himself mis-identified the stelae. Despite there being a still-extant stele in what used to be Roman Syria (it celebrates victories of pharaoh Ramesses II (ca. 1279-1213 BCE), not Sesostris), Whiston did not realise that the Greek word “Seirida” was used in late antiquity, not to refer to “Syria,” but rather to denote Egypt, the land of those who worshipped “Seirios,” our familiar “Dog Star,” Sirius (Latin).

Josephus would have been extremely loath even to hint that it might be construed that the descendants of Seth, with all their knowledge, were identified with the sciences of ancient Egypt. He makes it clear in his Antiquities that he believed the Egyptians received their science exclusively through Abraham who visited Egypt with his wife Sarai, whom pharaoh took a fancy to (note the “one-way” attraction).

My book identifies several sites that may have been understood nearly 2000 years ago as home to an antediluvian pillar belonging to a lost civilization, a time when, according to Genesis, there were sons of Adam, good and bad, “sons of God” who fancied human women, and “giants”; as well, of course, as “men of renown” or, arguably, fallen heroes – or angelic reprobates. The essential premise of the “lost pillars of Enoch” is that, namely, there was a time, before the Flood, when knowledge of God and knowledge of science were one.

The book next investigates how Josephus’s pillars of knowledge came to be associated with the names Enoch and Hermes. “Enoch” is of course Jewish, and “Hermes”, especially “Hermes Trismegistos” (Thrice Great Hermes, patriarch of wisdom) is Graeco-Egyptian, and to make the Jewish-Egyptian competitive issue even more interesting, we must contend with the fact that late antiquity was familiar with texts attributed to both these figures that purported to reveal truths about the origins of humankind and the intentions of God. And both figures were presented as having inscribed ancient knowledge to preserve it for future generations, in stories analogous, though not identical, to the Sethite pillar story related (without giving his source) by Josephus. The question of who came first is an open one.

Palestinian monk and episcopal servant George Syncellus, who died in about 810 CE, chronicled an account of Egyptian historian Manetho, supposed to have lived in the 2nd century BCE. Josephus was familiar with Manetho’s works, quoting them in his Contra Apion. However, not all works attributed to Manetho (such as the Book of Sothis) were written before Josephus’s time, and some may have been compiled or been tampered with, for propaganda reasons. The “Book of Sothis” concerns the dating of Egyptian dynasties (note the Sothis-Seirios reference). Here, Syncellus refers to it and its supposed author:

In the time of Ptolemy Philadelphus he [Manetho] was styled high priest of the pagan temples of Egypt, and [Note!] wrote from inscriptions in the Seriadic land [my italics; the Greek is “en tēi Sēriadikēi gēi”], traced, he says, in sacred language and holy characters by Thoth, the first Hermes, and translated after the Flood . . . in hieroglyphic characters. When the work had been arranged in books by Agathodaemon, son of the second Hermes [Trismegistos] and father of Tat, in the temple shrines of Egypt, Manetho dedicated it to the above King Ptolemy II Philadelphus in his Book of Sothis . . .

The natural question when confronted with this account might be to suppose Josephus had taken his Sethite pillar story from an Egyptian original and placed it among Sethites of culpable morals, where “Seth,” progenitor of wisdom, replaces Graeco-Egyptian Thoth, god of magic, whom Greeks identified with their god Hermes. Such would justify Apion’s accusation that Jews perverted Egyptian traditions. However, the specifically Hermes Trismegistos religious and philosophical literature (Corpus Hermeticum), which might support such a claim, are usually dated to the second and third centuries CE, post-dating Josephus. Besides, the first Book of Enoch had been long current when Josephus lived. In that work, Enoch preserves knowledge and delivers it to son Methuselah. It could be fairly argued that competitive Graeco-Egyptians transposed a Jewish story into a new Hermetic revelatory format. We just do not know, though the specific “pillar” element of the myth is, we may note, already identified by Josephus with Sirius worshippers (Egypt).

It is also the case that had Josephus been familiar with a story of Thoth inscribing wisdom in hieroglyphs before the Flood, which after the Flood were taken from tablets and put into books by Hermes Trismegistos—a kind of incarnation of deity Thoth—Josephus would certainly have believed the story was itself probably a lift from Moses’s account in Genesis of the wisdom of the descendants of Seth, because, as we have seen, Josephus was emphatic that Egypt gained its knowledge of astronomy from Abraham. Josephus would have regarded Sirius worship as just the kind of sin that caused the Flood in the first place: the kind of errant apostasy from the true God which left Egypt condemned by the prophets of the One God who insisted on tearing down pillars to other gods. One can easily see the complexities of this question! Josephus did not get the story from Genesis, but even if he obtained its rudiments from Egypt, it would have been natural and pious of him to translate them back into what he believed to be the authoritative, Godly narrative.

So, if an ancient pillar was venerated for antediluvian wisdom in “Seirida” (and there must have been numerous competitors for the dignity), then, in Josephus’s view, one was looking at the legacy of Seth’s inventive lineage, a special skein joined to the first Adam and blessed by God: an example to all who subsequently strayed from true religion and science, for, according to Jewish traditions, Egyptians, like all Gentiles, had been hostile to Jews because Gentiles anciently deviated from the original path ordained to those who “walked with God,” of whom the most remarkable, Genesis informs us, was Enoch, to whom we must now turn.

The name Enoch means in Hebrew something like “dedicated,” or even “initiated.” It was long a contender for association with Josephus’s pillars. On account of unique closeness to God, Enoch has been seen as archetype of Man Restored, a being with the knowledge to effect restoration of fallen humanity. In 1 Enoch chapter 81:1-3 we find:

And he [Uriel] said unto me:

“Observe, Enoch, these heavenly tablets,

And read what is written thereon,

And mark every individual fact.”

And I observed the heavenly tablets, and read everything which was written [thereon] and understood everything, and read the book of all the deeds of mankind, and of all the children of flesh that shall be upon the earth to the remotest generations.

Doesn’t this ring a bell with stories of Hermes Trismegistos imparting knowledge found on tablets in Egyptian temples? In 1 Enoch, Enoch is transported to earth to pass knowledge to son Methuselah, imparted subsequently to successive generations. This resonates with the relations Hermes enjoys with Agathodaimon in the Hermetica, a lost text of which (Physika) identifies Agathodaimon with “Chemeu,” divine founder of what we now call “alchemy,” a knowledge of sacred provenance intended to be secreted from the profane.

We know about Hermes’s alchemical text Physika from late third to fourth century CE alchemist, Zosimus of Panopolis. It is Zosimus who provides the first suggestion of possible conflation of Hermes and Enoch in a fragment of text from a work of his called “Imouth,” preserved by Syncellus. Zosimus refers to “Holy Scriptures” that refer to a race of demons availing themselves of women (strongly suggesting 1 Enoch’s take on Genesis 6). Zosimus notes that this is also mentioned in Hermes’s Physika.

Zosimus goes on to say that disgraced angels from heaven also brought with them knowledge of alchemy. Zosimus does not say the alchemy itself is evil, but laments its perversion into “unnatural” forms dependent on demonic participation, while knowledge of the “natural” tinctures remains reserved for spiritually enlightened or reborn souls, respectful of sacredness and in tune with God.

After the rise of Islam we find “Sabians” in Harran in the eighth and ninth centuries honouring the Hermetica as scripture. They regarded Hermes and Enoch as the same person. Arabic-speaking scholars identified Hermes-Enoch with Idris in the Koran. The most brilliant astrologer of Baghdad’s Abbasid court, Abu Ma‘shar Ja’far ibn Muhammad ibn ‘Umar al-Balkhi (787–886), confirms this, identifying sage Hermes not only with Enoch, but also with the Iranian “Adam,” Kayumarth.

By the eleventh century, evidence from Moorish Andalusia shows the belief that it was Enoch himself who, hearing of the Flood to come, constructed Egypt’s temples and pyramids to preserve threatened knowledge (Sāid al-Andalusī (1029–1070), Tabaqāt al-᾽Umam, “Categories of Nations,” 39.7–16). In the same period, an Orthodox Christian collection of ancient texts, the Palaea Historica, explicitly identifies the fashioner of the tablets of knowledge on marble and brick with the righteous Enoch.

The middle ages inherited the idea that the figures Enoch and Hermes were essentially one historic person, perceived by different traditions but united in dedication to the purposes of God.

The mighty influence of these traditions is traced through history to our own day. The Lost Pillars of Enoch demonstrates the theme of an antediluvian, effectively lost civilization (though often closely identified with an Hermetic-style Egypt—its product, so to speak), as one of the great motivators in the development of western thought, while the image of the “lost pillars” itself becomes a kind of epitome, or even symbol, of a transforming, elevating knowledge, material and spiritual, passed to the future.

Now we can look again at Hermetic influence within Renaissance thought in the persons of Ramon Llull, Marsilio Ficino, Pico della Mirandola, Francesco Giorgi, Giordano Bruno, Copernicus, and later John Dee and the first “Rosicrucian” explosion in the early seventeenth century. All these people were impressed by the idea of a prisca theologia or “ancient theology” that went back to Adam, before the Flood, and which had, in part, been preserved by a Hermes equated with Enoch.

This supposed antediluvian knowledge was considered to underlie all subsequently divided knowledge, maintaining the keys to unite all sciences in a unified system operating on multiple planes and pointing to a single divine origin, accessible to enlightened mind that could henceforth pump forth new insight into truth like a fountain. We can see how Copernicus justified his heliocentric science by astute reference to Hermes, through whom knowledge of the sun’s centrality descended through largely forgotten antique theories of Pythagoras’s pupil Philolaus and of Aristarchos of Samos (ca. 310–ca. 230 BCE). Pristine knowledge was returning to earth to free humankind from spiritual darkness and ignorance.

My book next details the place of Enoch and Hermes—and of the “pillars of Enoch” (seen as originally more significant than the pillars of Solomon’s Temple)—in the formation of a pre-Grand Lodge Freemasonry. At the heart of Freemasonry lies a search for something lost. We explore a profound mysticism present within the London Company of Freemasons in the period when, on the continent, a great ferment was stirred by pirated publications of the so-called “Rosicrucian” manifestoes, auguring an open brotherhood of knowledge.

A careful treatment of Isaac Newton follows, with due emphasis on his alchemical research and fundamental belief that what he was credited with discovering was in fact the privileged knowledge known, not only to a known Philolaus, but to a largely unknown antiquity whose science and religion were one, as Newton intended ours to be. Stephen Snobelen, director of the Newton Project, Canada, insists that Newton’s theological writings were equally important to Newton as was his natural philosophy. Newton’s overarching concern was “the restoration of man’s original pristine knowledge of God and the world.”

The final chapters offer my integrated thought on the possibility of a fresh impulse to reunite science and religion based on an understanding of the esoteric strands within Paganism, Hinduism, Judaism, Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam, amid the numerous theosophies drawing on aspects of each. The book locates the spiritual unity of Hermetic thought, Advaitist jnana-yoga, Kabbalah, Zen, Gnosis, Sufism, and the varied branches of modern “western esotericism.”

From the perspective acquired in this book, the future is not one of “lost pillars” but of pillars re-found, and even understood, for those with the eyes to see them.

Tobias Churton is a member of the “Enoch Seminar,” organized by Professor Gabriele Boccaccini, professor of Second Temple Studies at the University of Michigan. Churton’s paper on Freemasonry and the Book of Enoch was delivered at the Enoch Seminar held in Florence, summer 2019.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|